By John Tierney and James McKeon

Editor’s note: This article is cross-posted on Just Security.

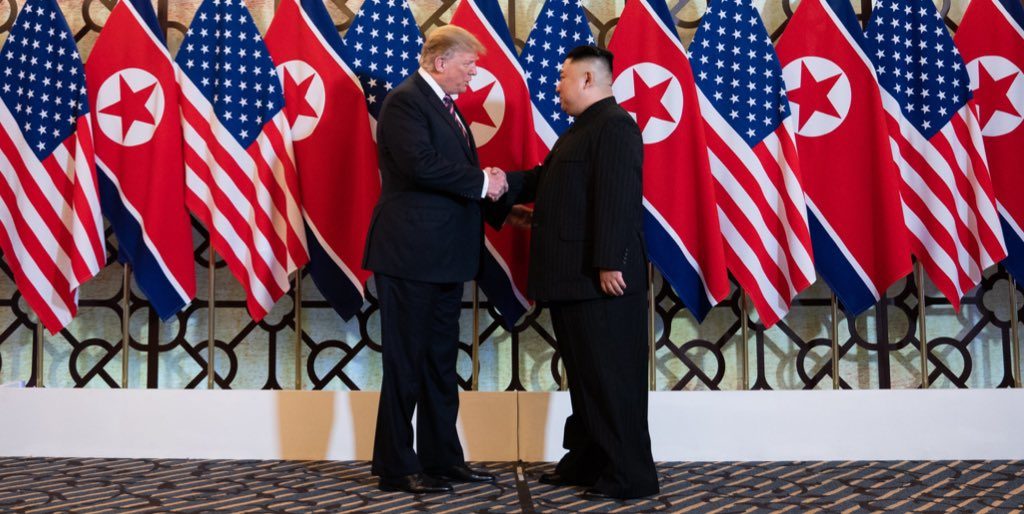

In the weeks since the end of the Hanoi Summit, competing narratives have emerged between the United States and North Korea. The Trump Administration stated that President Trump unsuccessfully pushed North Korea to “go bigger” and dismantle much, if not all, of its nuclear and missile infrastructure in exchange for targeted sanctions relief. North Korea, by contrast, argued that it offered to dismantle all of its main nuclear facility (Yongbyon) in exchange for partial sanctions relief (portions of international sanctions enacted since 2016).

In the weeks since the end of the Hanoi Summit, competing narratives have emerged between the United States and North Korea. The Trump Administration stated that President Trump unsuccessfully pushed North Korea to “go bigger” and dismantle much, if not all, of its nuclear and missile infrastructure in exchange for targeted sanctions relief. North Korea, by contrast, argued that it offered to dismantle all of its main nuclear facility (Yongbyon) in exchange for partial sanctions relief (portions of international sanctions enacted since 2016).

The differing narratives underscore the complexity of nuclear negotiations. But rather than rehash what has transpired, a more productive route involves considering options going forward. Both parties left Hanoi in a somewhat conciliatory mood, and continuing discussions seem to be on the table. That is certainly positive, but only if the Trump Administration adequately prepares for a path forward that does not involve maximalist demands and bypasses another Trump-Kim summit until tangible progress has been made at the diplomatic working level.

First, some reality. Despite President Trump’s assertion that North Korea’s nuclear program is no longer a threat, the truth is that Pyongyang continues to expand its fissile material production. At the same time, however, North Korea has also continued its freeze on nuclear and missile testing, a positive confidence-building measure that at least partially restricts further progress on ICBM and thermonuclear development. Pyongyang has also destroyed its nuclear testing site at Punggye-ri, though the extent of the destruction has yet to be verified. On the other side, the United States has halted large-scale joint military exercises with South Korea. Add in multiple meetings between South Korean President Moon and North Korean leader Kim, and partial demilitarization on the heavily militarized North-South border, and one thing is clear: tension on the Korean Peninsula has been greatly reduced, especially compared to threats of “fire and fury” from less than two years ago.

Considering the result of the Hanoi Summit, how long can this reduced tension last? Under any circumstance, it is not in the United States’ interest to increase tensions and risk unviable military options. Likewise, it is politically and strategically unviable to continue talks indefinitely with no tangible results toward denuclearization or peace on the Korean Peninsula. Thus, the roadmap forward must involve further negotiations that take into account North Korea’s concerns and focus on achievable, phased steps to denuclearization.

Here’s how that might look. First, the United States should move away from the Donald Trump reality TV portion of the process and into efforts led by empowered, experienced, and knowledgeable technical experts and diplomats to engage with their North Korean counterparts. Stephen Biegun, the U.S. Special Representative for North Korea, should be given the authority to lead the negotiations. President Trump should stay out of the process until tangible progress is made.

Second, the goals of these renewed talks should not be unrealistic demands for immediate denuclearization, but instead a phased, step-by-step approach that involves practical concessions on both sides. This process starts with U.S. messaging. Mr. Biegun, for example, has on one hand argued for a phased approach but then, weeks later, a senior Administration official stated, ”nobody in the administration advocates a step-by-step approach.” Mr. Biegun then reiterated the latter approach when he publicly declared, “We are not going to do denuclearization incrementally.” Such an inconsistent and maximalist approach will only end in failure. Instead, the United States should focus on locking in the North Korean freeze to nuclear and missile testing and pressing for an end to the production of fissile and related material, such as plutonium, highly enriched uranium, and tritium.

The next step would involve the verifiable dismantlement – ideally led by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) – of the Yongbyon nuclear complex. While not completely solving the North Korean nuclear issue, the verifiable closure of Yongbyon would severely reduce North Korea’s future nuclear capabilities and build confidence that Pyongyang’s interest in denuclearization is real and tangible. North Korea’s nuclear and missile programs are complex and dispersed throughout the country, including numerous so-called undeclared facilities. Nonetheless, the process of real, verifiable denuclearization will not begin without Yongbyon, and that should be the initial focus of American negotiators. What comes afterward would be subject to the confidence and effective implementation of an interim agreement to close Yongbyon (and anything else agreed upon).

Of course, North Korea won’t agree to such concessions without some reciprocation from the United States. This could include one or more of the following: A “declaration of peace” that unofficially ends the Korean War, formal commitments to cease joint exercises for a defined time period, and limited, commensurate sanctions relief (this is the most difficult to define, but numerous options are available under both US and UNSC sanctions). Further inter-Korea economic cooperation could help to underpin any progress made.

None of this may come to pass. But any suggestion that the only alternative to effective agreements is military action must be shut down. While some may dream that military action would force North Korea to instantly give up its weapons systems and remove the regime, the reality is dire. Hypothetical assessments point to American and South Korean casualties in the hundreds of thousands — and that’s assuming the conflict does not go nuclear.

Negotiators must now look forward, not backward. Regardless of the competing narratives of the Hanoi Summit, both sides have strong incentives to return to the diplomatic table and attempt to find a path forward. President Trump alone is not capable of negotiating what inevitably would be one of the most complex nuclear agreements in history. Today, after two major summits, it is long past time to empower the strong cadre of American technical and diplomatic experts to take the lead on transforming reduced tensions into verifiable agreements.