By Daniel Wirls, Professor of Politics, UC Santa Cruz

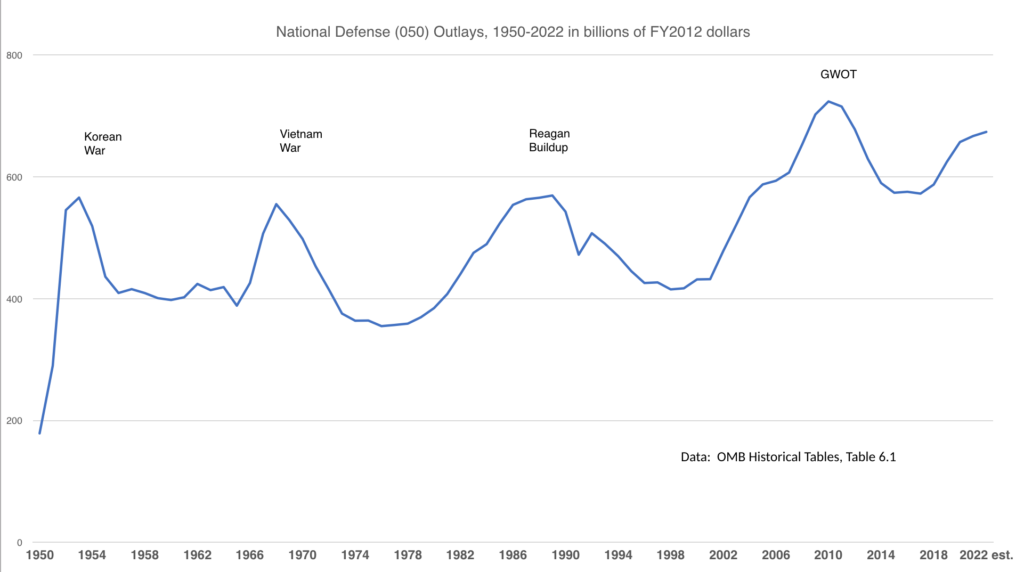

The Biden National Defense budget presented to Congress in late January 2021 is a modest increase from the previous year but among the highest in the last 70 years in constant dollars adjusted for inflation – despite the effective end to the forever wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

It is higher than peak spending for the Korean War, the Vietnam War and the Reagan buildup, and only slightly below 2011, the most expensive year during the so-called Global War on Terror. In fact, Biden’s first military budget request is about $40 billion more than the average annual spending during core decade (2003-2012) of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

One of the principal justifications for this level of spending is the recent “discovery” of a military threat from an emerging China, which has become the new Soviet Union and what the Secretary of Defense calls the “pacing” threat for high spending.

There has been a pattern in history driving the military budget upwards. The United States loses in Vietnam, only to immediately rediscover the Soviet threat. The Cold War ends, and policy makers invent “rogue states” including Iraq and Iran. The United States engages in the forever wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, with poor results. Now that the U.S. is completing withdrawal from Kabul, the government is reinventing the Cold War based on the recent perception of China as a major threat. It is always, in the minds of national security folks, a more unstable and unpredictable strategic environment.

The chart shows that defense spending has been cyclical, falling modestly after each period of crisis. Manufacturing new threats and crises to drive up spending not only saddles taxpayers with unsustainable costs, but short circuits a full reevaluation of the needs of the military.

Another pattern is that the peak years of every military buildup, whether during war or peace, become the anchor point for assessing any “reductions” in military spending. Just as the peak of the Reagan buildup became the standard against which to judge and criticize post-Cold War cuts, the peak of spending in the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan will be the irrational standard against which to judge and criticize any potential efforts to reduce or rationalize military spending under Biden. The Pentagon and Congress became accustomed to the kind of spending that accompanied the wars and the Trump administration spent four years reversing some of the war-related reductions under Obama. The Biden defense budgets are likely to be judged largely against this baseline of extravagant military spending.

History shows that threats are found and hyped to justify the budgets the Pentagon, and much of Congress, wants rather than budgets being defined by serious assessments of what we really need.