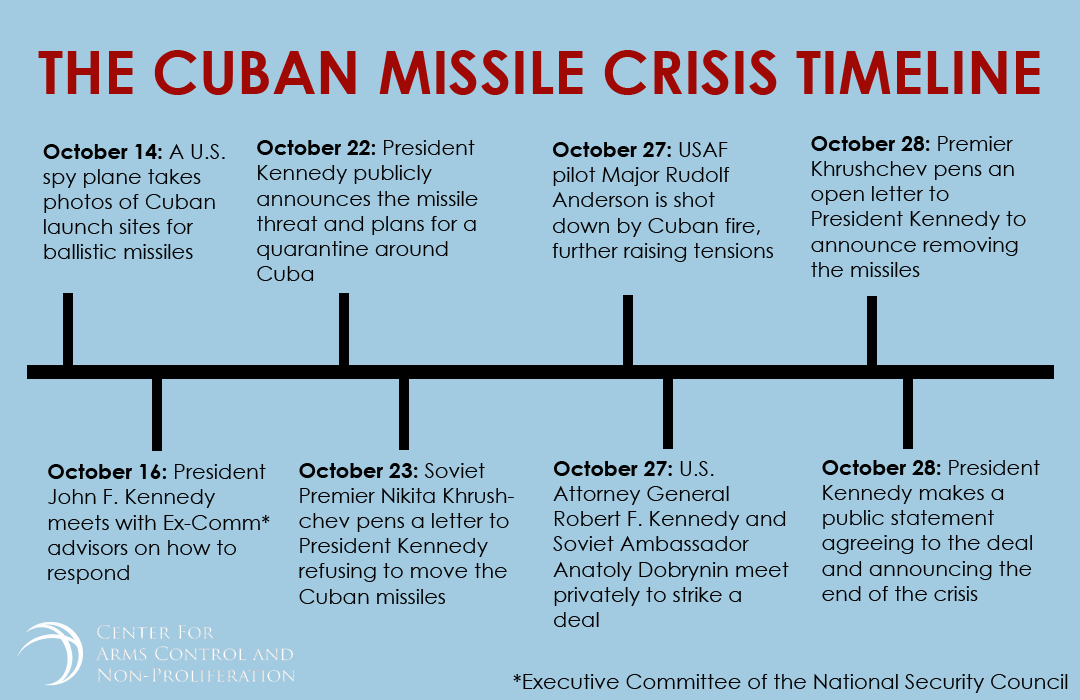

For approximately 13 days in October 1962, beginning on October 16, the world stood on high alert amidst a crisis of unprecedented proportions. Photographs taken by an American U2 spy plane revealed suspicious construction activity across Cuba, later confirmed by a low-flying RF-8As to be the installation of Soviet nuclear missiles and infrastructure. The CIA’s National Photographic Interpretation Center quickly identified these medium and intermediate-range missiles as the SS-4 SANDAL and the SS-5 SKEAN. Both missiles were capable of striking American territory.

President John F. Kennedy’s options were limited, and the timeline until the missiles became operational was shrinking. Declassified documents reveal that the Joint Chiefs advocated strongly for an immediate military response followed by an attempt to remove Cuban President Fidel Castro from power. Others, like Secretary of State Dean Rusk, urged diplomacy. Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara floated a naval blockade as a possible alternative course of action.

President John F. Kennedy’s options were limited, and the timeline until the missiles became operational was shrinking. Declassified documents reveal that the Joint Chiefs advocated strongly for an immediate military response followed by an attempt to remove Cuban President Fidel Castro from power. Others, like Secretary of State Dean Rusk, urged diplomacy. Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara floated a naval blockade as a possible alternative course of action.

The President was worried about a possible nuclear exchange, and ultimately decided to pursue a blockade. However, since a blockade was legally an act of war, he labeled the action as a “quarantine.” The quarantine came alongside several communications to Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev demanding the removal of all offensive weapons in Cuba, and a televised appeal to the nation linking any use of force in the western hemisphere to the Soviets.

Khrushchev viewed the quarantine as an ultimatum, a perception that JFK’s taskforce had hoped to avoid. In a letter penned to JFK, he called U.S. actions an “open violation of international law under the U.N. Charter.” Khrushchev ordered his ships to continue their journey to Cuba, and since there were no weapons on board, the U.S. Navy permitted them to proceed. Castro, fearing a U.S. invasion was imminent, privately urged Khrushchev to launch a preemptive nuclear strike against the Americans. His pleas went ignored.

On October 27, Cuban soldiers shot down a U.S. plane carrying out a reconnaissance mission. The pilot, Major Rudolf Anderson, was killed. The crisis had reached a turning point. Kennedy could now argue that the Soviets had fired on the United States first, granting him the legal authority to conduct a counterstrike. He began preparations for a military response, but insisted on maintaining clear lines of communication with Khrushchev. The door to diplomacy remained open, despite the sense of war being inevitable.

As a last-ditch effort at peace, Attorney General Robert Kennedy and Soviet Ambassador Anatoly Dobrynin met privately later that evening to discuss remaining avenues for cooperation. Fortunately, they struck a deal. The Soviets agreed to remove their offensive missiles from Cuba if the United States promised to remove its Jupiter missiles from Turkey, and not to invade Cuba. The next day, Khrushchev and President Kennedy announced the agreement separately, ending the crisis.

For further reading on The Cuban Missile Crisis, we recommend these titles:

One Hell of a Gamble: Khrushchev, Castro, and Kennedy, 1958-1964.

John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum Homepage, “Cuban Missile Crisis.”

Thirteen Days: A Memoir of the Cuban Missile Crisis.

The Kennedy Tapes: Inside the White House During the Cuban Missile Crisis.

National Security Archive Homepage. “The Cuban Missile Crisis, 1962.”