Guest Post by Alex Bollfrass

News broke last week that prosecutors are asking to have William Jefferson (D.-Louisiana) locked up for some 13 years. You may remember that he stashed about $90,000 in dirty money in his freezer.

If you thought that a bribe to a foreign vice-president was the most unappetizing thing stuffed in with the pie crusts, read Thomas Schelling’s “A world without nuclear weapons?” in the current issue of Daedalus (gated). In his telling, one of the major barriers to a world without nuclear weapons is his refrigeration capacity:

“[E]nough plutonium to make a bomb could be hidden in the freezing compartment of my refrigerator.”

While this observation about the size of the plutonium in a nuclear bomb may be true, it tells us little about the feasibility of nuclear disarmament.

Schelling’s point is that if sufficient fissile material for a bomb is small enough to fit into a freezer, an agreement to eliminate nuclear weapons could never be verified. But hiding weapons is only part of a cheater’s problem. There are additional formidable obstacles that would prompt anyone contemplating reconstituting or developing nuclear weapons in a disarmament regime to think very carefully.

Cheating on a disarmament agreement could happen in one of three ways:

1. Cheating at the outset and retaining undeclared warheads or fissile materials;

2. Clandestinely producing the materials for a nuclear arsenal after disarmament had been accomplished;

3. Diverting declared materials from nuclear energy facilities or from left-over fissile material stocks.

The last method is roughly equivalent to grabbing the money and dashing for the casino door. The ploy would be immediately uncovered as all such facilities and stockpiles would be safeguarded far more closely than ex-Congressman Jefferson’s “take” in any self-respecting disarmament regime. Such a cheater’s gain, if any, would be short-lived. Either the other signatories would undertake collective action with conventional military forces to stop the program, or those with the potential capabilities would rearm themselves, leaving the world no worse off than it is now. A rearmament effort triggered this way would be unfortunate, but unlikely. Furthermore, it would be comparatively stable because the governments would be building a defense-oriented deterrent, as opposed to seeking a coercive advantage.

The middle course of action? Check with this bloke. With on-site challenge inspections and national means of verification, such an action would likely be discovered relatively quickly, just as the Qom facility was uncovered and has every covert weapons program to date. The world may not have acted on South Africa’s or Israel’s or Pakistan’s covert weapon programs, but the United States and others were certainly aware of what was going on – even without an on-site challenge inspection scheme.

The first option, Schelling’s path, is only available to the nine countries that already have enough unsafeguarded plutonium or highly enriched uranium to make a bomb: China, France, Great Britain, India, Israel, North Korea, Pakistan, Russia, and the United States.

In practice, the majority of these countries would almost certainly be caught. Their holdings of materials are modest enough that their declarations of weapons and stocks could be confirmed with great certainty using a combination of forensic verification techniques. The only two exceptions are the US and Russia, both of which produced massive amounts of fissile material during the Cold War. For these two exceptions, the margin of error that could reasonably be expected from thorough verification procedures amounts to several hundreds of bombs worth of uncertainty. If we agreed to implement nuclear disarmament tomorrow, we or the Russians could presumably squirrel away at least several dozen bombs (or at least the fissile materials to make them).

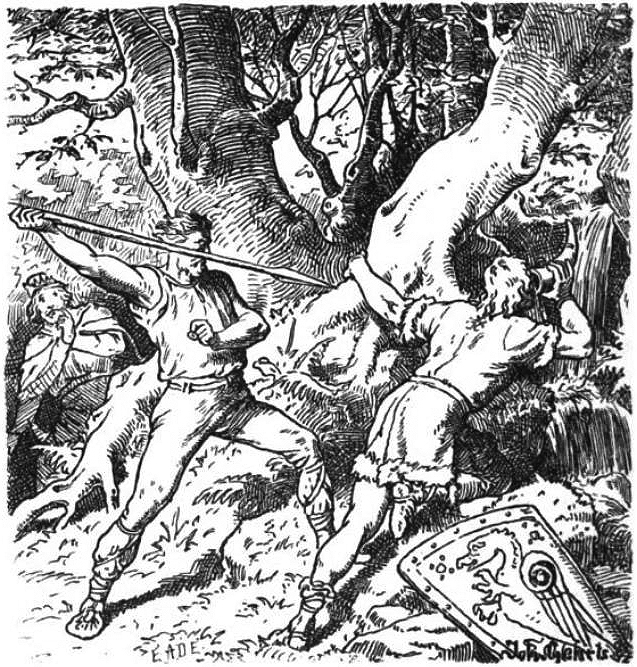

Will this prove to be nuclear disarmament’s fatal vulnerability – a la Siegfried’s exposed back?

It need not be. That margin of error can be reduced by an increase in transparency, coupled with the healing powers of time. Long before moving to the White House, Steve Fetter wrote “Verifying Nuclear Disarmament” as the Stimson Center’s Occasional Paper #29 in 1996. He identified a remedy, which is worth quoting at length from the paper:

A data exchange could help build confidence between the parties even before the accuracy of the data was verified. An early exchange of data is particularly important because it would force governments to make decisions about compliance with reporting requirements well in advance of possible disarmament agreements. A government that possesses thousands of nuclear weapons and has made no near-term commitment to disarmament is less likely to be suspected of falsifying records or hiding weapons than a country that has few weapons and is obliged to eliminate the remainder, simply because a country with thousands of warheads would have little incentive to cheat.

It is also important to begin verifying declarations as far in advance of a disarmament agreement as possible. As the number of nuclear weapons falls into the hundreds, states would be far more likely to have confidence in a declaration whose accuracy had been verified for years and for tens of thousands of nuclear warheads, than one whose verification had begun only recently and only after thousands of warheads had been dismantled. Failure to verify the dismantling and consolidation of the huge US and Russian nuclear stockpiles could undermine severely the two sides’ confidence in a declaration made later about much smaller numbers of weapons. There is little pressure for warhead-verification today because current and planned stockpiles are so large as to make existing uncertainties unimportant. But unless the nuclear powers begin now to describe and verify their warhead stockpiles, when the need for verification is not pressing, they will have failed to lay a foundation that is strong enough to bear the weight of a disarmament regime.

Data on the history of stockpiles and the operation of warhead-related facilities cannot be verified directly, of course, but it could be checked for internal consistency, and for its consistency with archived intelligence data. If, for example, US satellites had detected the movement of nuclear warheads from a particular Russian facility on a particular date in the past, this could be checked against the records exchanged between the two countries. Indeed, such records should improve the value of archived data by confirming or contradicting past interpretations by intelligence agencies. The fact that countries would not know what intelligence information might be available would act as an incentive to provide complete and accurate data.

As with declarations on delivery vehicles, data on the current status of nuclear warheads would be verified by regular and short-notice inspections of declared facilities, combined with challenge inspections to verify the absence of warheads at other locations. For example, inspectors could count the number of warheads in a particular storage bunker and compare this to the number listed in the data exchange.

If President Obama sees nuclear disarmament as a serious destination, and not just rhetorical decoration for traditional arms control and nonproliferation, these kinds of early transparency measures should be included in the next round of negotiations with the Russians. So should tactical nuclear weapons.

In the most optimistic abolition scenario, ex-Congressman Jefferson would find himself released into a world contemplating the final destruction of the remaining nuclear weapons when he retires as ex-convict Jefferson several decades from now. That is a long time to devise technologies and procedures for verifying US and Russian fissile material stocks. Whether the nuclear-armed countries of that era will have the confidence to take such a leap depends on how seriously we prepare for this possibility in the next few years.

Alex Bollfrass works for the Unblocking the Road to Zero project at the Stimson Center, where he occasionally comes across suspiciously plutonium-like materials in the office refrigerator.