The United States is headed for trouble, according to Walter Pincus of the Washington Post, in his recent article “War, hot or cold?” The crux of the issue: the U.S. is balancing military spending for two non-complementary styles of war. On the one hand, the U.S. is developing its intelligence and armed forces to fight a “hot war” against terrorist groups such as al-Qaeda and the Islamic State; on the other, the U.S. is developing costly weapons programs to ensure superiority in a Cold-War-style standoff with Russia and China. As Pincus is concerned, funding both styles may not be practical or affordable, meaning “Americans have some tough choices ahead.”

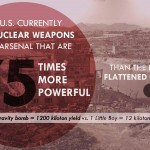

“These days, terrorists are the first threat,” says Pincus, “and not a single one will be deterred by a nuclear warhead.”