Reflections on my trip to Los Alamos

By Anna Schumann

On July 16, 1945, the nuclear age began when a team of Manhattan Project scientists working in Los Alamos, New Mexico, tested the first nuclear bomb, dubbed the Trinity Test, after years of building it in secret.

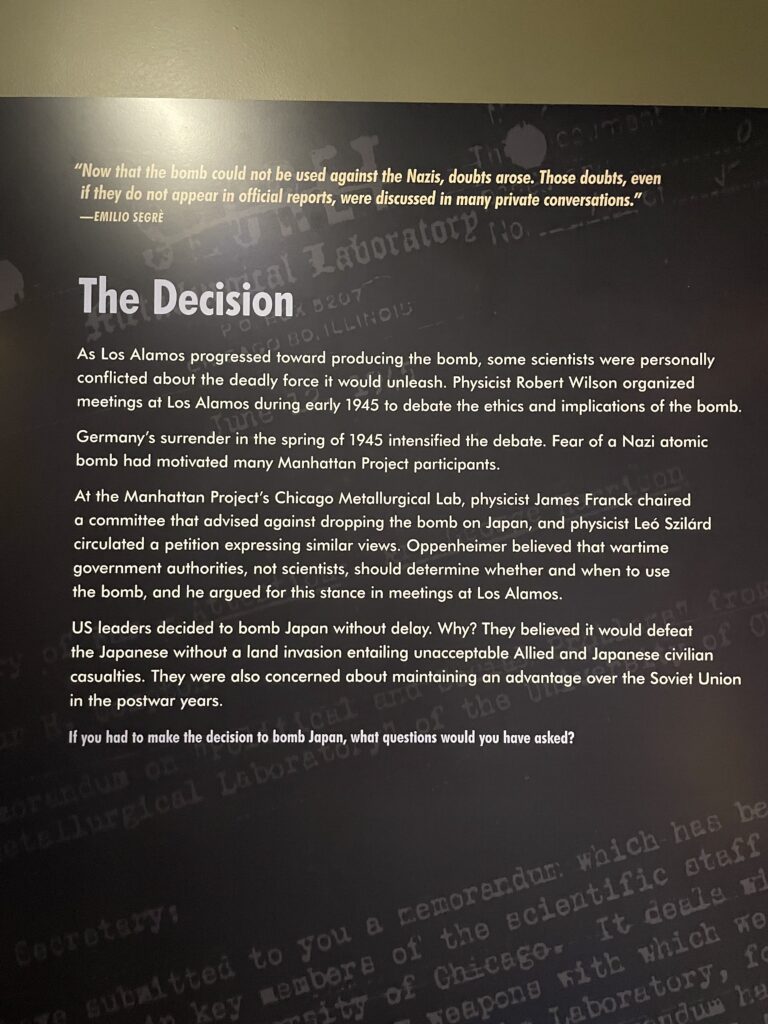

On July 17, 1945, the anti-nuclear age began in earnest when many Manhattan Project scientists banded together to urge the government not to use a nuclear bomb against Japan without allowing it to surrender, warning of “an era of devastation on an unimaginable scale.”

These scientists, including our sister organization’s founder, Leo Szilard, had met privately in the months leading up to July 16 to raise objections about the bomb’s use. Szilard had been circulating drafts of the petition he ultimately sent to President Harry Truman for nearly two weeks and had privately discussed his concerns about the potential of atomic weapons for years. But on July 17 and in the weeks that followed, Szilard’s advocacy against the bomb and arms racing accelerated and would become a defining characteristic of the remainder of his life. And he wasn’t alone.

In 1962, Szilard founded Council for a Livable World, which had many of his fellow Manhattan Project scientists as early board members. His colleagues at the Chicago Metallurgical Laboratory founded the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists and colleagues at the Los Alamos and Oak Ridge sites founded Federation of American Scientists in 1945. These giants of the anti-nuclear movement all continue to call for nuclear restraint.

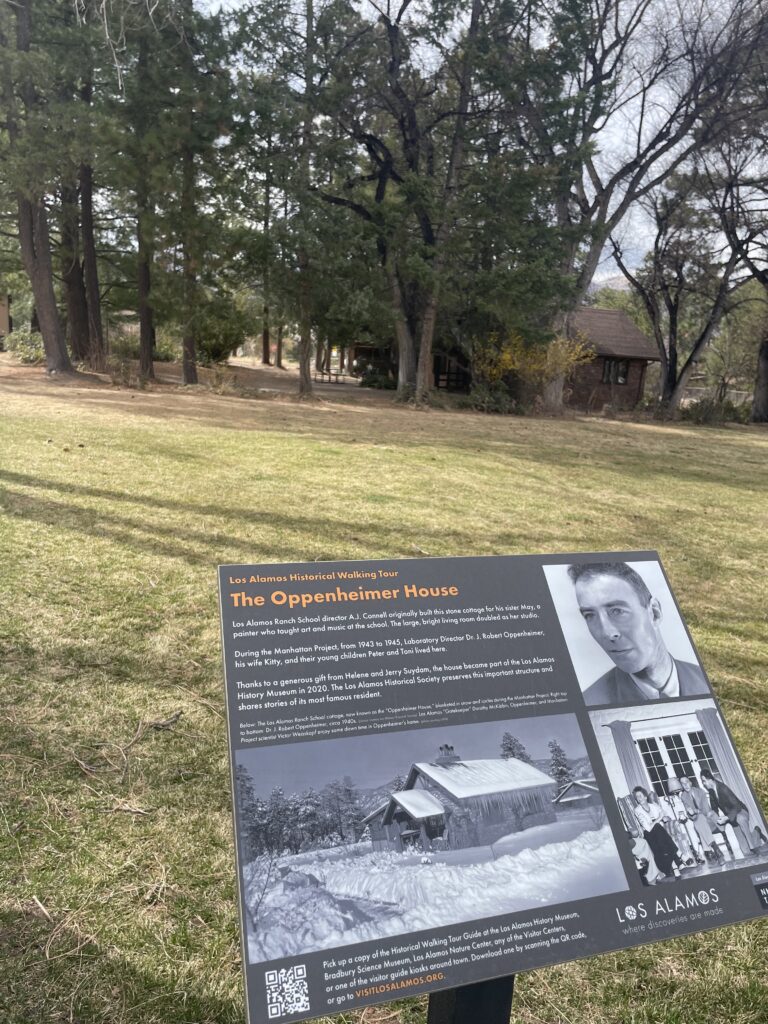

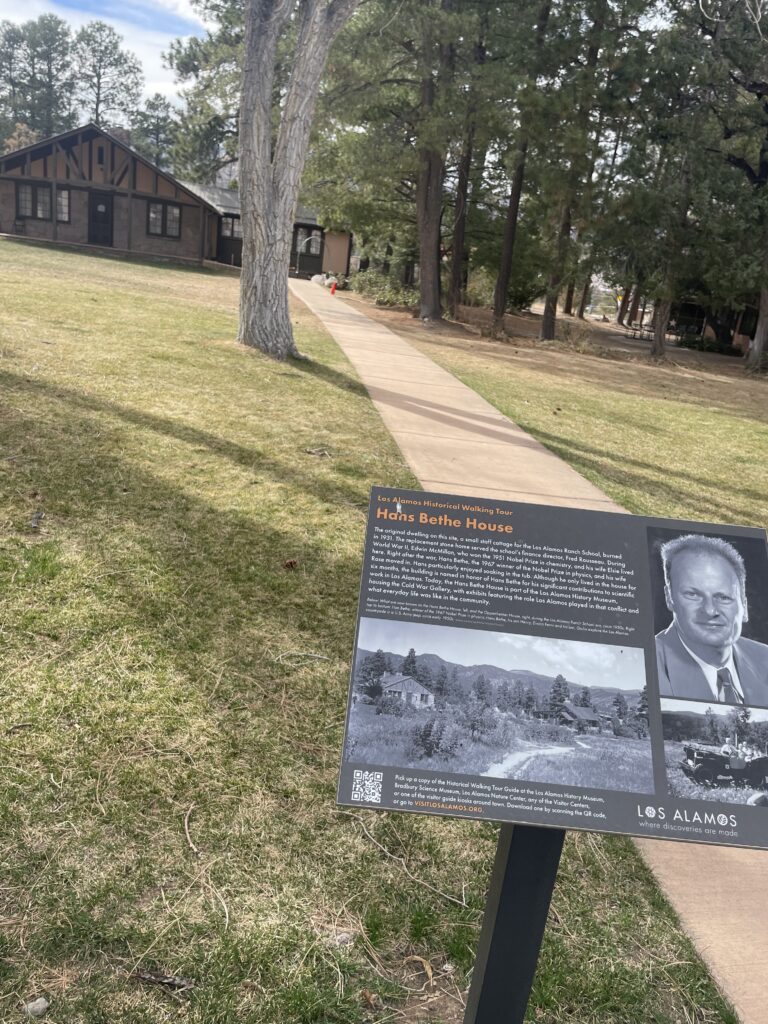

In March, 80 years after the dawn of the nuclear and anti-nuclear ages, I traced their footsteps at the birthplace of the bomb — Los Alamos, New Mexico. I was eager to see with my own eyes places I’d only read about and seen old photos of, yet mindful that I wanted to acknowledge, not celebrate, the tragic outcomes created in this isolated mountain town.

I wasn’t sure what to expect on this spontaneous trip. Would these museums and historical sites acknowledge the destruction of the bombs created here, or would they only celebrate the scientific feat? Would these museums discuss the scientists’ objections to the use of nuclear weapons, or would they only honor the work of the people who put their small town on the map? Would they treat nuclear weapons as an ongoing threat to humanity, or would they only talk about them as relics of a bygone era?

My tour began at the Los Alamos History Museum, which houses artifacts and exhibits that take guests through the history of the land going back to Indigenous people 1,000 years ago, to homesteaders in the 1800s, to the Los Alamos Ranch School that would be taken over by the Army for the Manhattan Project in the 1940s.

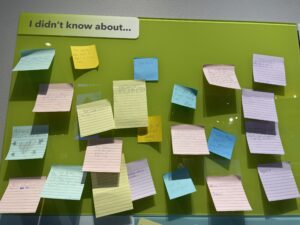

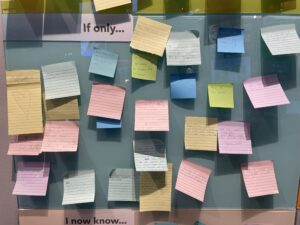

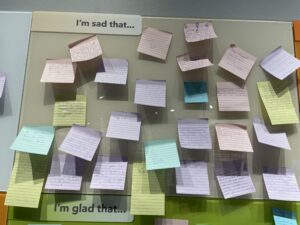

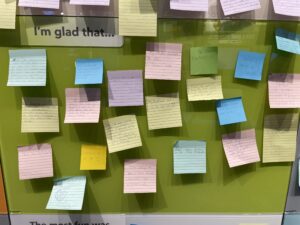

The last stop was the Bradbury Science Museum, the official museum of the Los Alamos National Laboratory, which features exhibits on past and present nuclear weapons, the mechanics of the bomb and more historical artifacts. But my favorite part by far was what they call the public forum — a series of prompts on a wall that encourages visitors to share their thoughts about what they learned via sticky notes. I read and took pictures of every single one (some pictured below).

People expressed surprise about the size of bombs and the Manhattan Project’s jobs for women; longing for more public education on nuclear weapons, more research into the consequences of nuclear bombing before their use and less money spent on war; sadness over the lives lost to nuclear testing and use in warfare; and gratitude for science.

I didn’t agree with every takeaway people shared, but reading people’s perspectives on visiting Los Alamos made me think about what the Manhattan Project scientists felt leading up to the Trinity Test, then between the release of Szilard’s petition and the U.S. bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and then after that, when they embarked on missions to rid the world of the weapons they helped create. Not every scientist who worked on the bomb shared Szilard’s belief that nuclear weapons should be restrained, or that it was a scientist’s job to advocate one way or another, just like the different opinions on nuclear weapons in the public forum.

The notes in the public forum made me think about the fact that progress — in this case, away from nuclear arms and toward nuclear disarmament — is not always linear.

On July 16, 1945, the nuclear age began with a massive explosion. On July 17, dozens of Manhattan Project scientists petitioned the president not to use nuclear weapons — progress. On August 6 and 9, the United States dropped bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, killing hundreds of thousands of people and dooming survivors to lives of health issues and societal stigma — huge setback. Within months, scientists founded two large organizations advocating nuclear restraint that are still giants in the community today — progress.

Four years later, the Soviet Union boasted its own nuclear arsenal — setback. By the time the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty went into force in 1970, it was expected that the world would have more than 25 nuclear powers; today, there are nine. By 1986, there were more than 70,000 nuclear weapons in the world — setback. Today, there are about 12,200 — progress. In February, the last remaining treaty restricting the U.S. and Russian arsenals will expire with nothing to replace it — setback.

Will the next step take us in the right or wrong direction?

While we spend July 16 of every year acknowledging the dawn of the nuclear age, now, 80 years in, I want to make sure we spend just as much time talking about the dawn of the anti-nuclear age, all the progress we’ve made and all the progress that’s yet to come. Working toward a world free from nuclear threats has not been without its setbacks, but thanks to diplomacy and arms control, we’ve already eliminated more than 80% of the nuclear weapons that have ever existed. That’s tremendous progress. Together, let’s finish the job. For the next milestone anniversary, let’s make sure we’ve moved more toward disarmament than an arms race.