By Anna Schumann

I walked into the room at the top of the stairs and saw a seemingly endless stream of bodies lying there, flat on the ground, as the peaceful sounds of leaves and insects filled one ear, and the aggressive sounds of construction filled the other. It was disruptive to hear them both at once.

I could see the bodies, helpless, contorted, some with visible reactions still on their faces and their arms extended in front of them — as if more skin and bones would protect them. They didn’t know it was coming. They had nowhere to run.

Suddenly, the sounds of construction turned to a man’s voice. Muffled, but not distant. I couldn’t tell what he was saying, but something had happened. Something had changed. I circled each body, one by one, trying to put myself in their places. Where were they heading when it happened? What were their life goals? Did they have kids? Did their kids die too?

Another family came into the room as parents quietly explained to their young children why they should be silent and respectful in a place like this. A little boy and his dad weaved between the bodies. A little girl and her mom sat on the benches nearby and I could tell by looking at her that she was thinking about what was happening.

They left after a few minutes; I stayed a little bit longer, taking in the sights, sounds and meaning of what I was experiencing. Then, I talked to the man who put the bodies there.

Kei Ito is the grandson of a man who was a teenager living in Hiroshima when the United States used the first nuclear weapon in combat. Ito grew up in Japan, and can understand better than most the real and lasting effects of a nuclear weapon.

When Ito discovered in 2014 that his housemate also struggled with his family’s nuclear bomb experience — though on the opposite end of the spectrum, as Andrew Paul Keiper’s grandfather worked on the Manhattan Project — the two art students knew they had to do something.

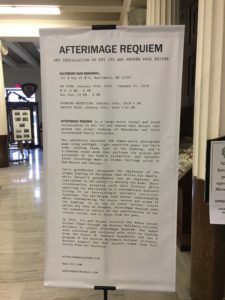

Afterimage Requiem, an exhibit that was hosted at the Baltimore War Memorial last month, is an immersive visual and audio experience. Each body is a photograph of Ito, contorted into different positions: sometimes fetal, sometimes flat on his back, all representing the moment at which many residents of his grandfather’s hometown were incinerated.

Keiper was responsible for the audio portion of the exhibit. He said sounds were primarily recorded at the Trinity site in southern New Mexico, the site of the first nuclear test. The natural sounds include leaves rustling, insects buzzing and a birdsong in a ravine. The industrial sounds represent the production of the bomb itself: the simulated uranium enrichment process; the building of various facilities; and a recording of Keiper reading selections from The Los Alamos Primer.

The dichotomy of peaceful and industrial sounds, Keiper said, is meant to “braid together an experience that sways between the symbolic, the documentary, and the dramatic.”

Ito said while the artwork is based on the artists’ families’ relationship to the Hiroshima bombing in 1945, he hopes it is a starting point to talk about the more modern nuclear crises.

“The art work acts as a reminder and a warning, but at the same time the work is the embodiment of hope in people’s will to create a better world where the peace doesn’t rely on a fragile concept such as a nuclear deterrent.”

Ito and Keiper hope to have the exhibit travel nationwide, but right now, there are no plans for its next location. Let’s hope that changes.