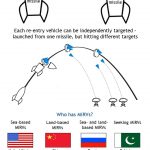

Updated March 2021 Multiple Independently-targetable Reentry Vehicles (MIRVs) were originally developed in the early 1960s to permit a missile to deliver multiple nuclear warheads to different targets. In contrast to a traditional missile, which carries one warhead, MIRVs can carry multiple warheads. For instance, a Russian MIRVed missile under development may be able to carry […]

Fact Sheet: Global Nuclear Weapons Inventories in 2014

Prepared by Lesley McNiesh Updated by Justin Bresolin, Sam Kane, and Andrew Szarejko CHART: Global Nuclear Weapons Inventories, 2014 Nuclear weapons programs are generally shrouded in secrecy and all of the totals listed above should be considered estimates. The numbers in the chart above are based on the most recent available estimates from the Bulletin […]

Pakistan’s Nuclear Buildup: The End of US ‘Strategic Silence’?

While most nuclear weapons states around the world have reduced their nuclear weapons stockpiles in recent years, Pakistan has been rapidly expanding its nuclear arsenal. Current estimates place the country’s stockpile at 100-120 nuclear warheads, up from 70-90 in 2010. If this trend continues, the country will have a larger nuclear weapons stockpile than the United Kingdom, which has approximately 225 warheads, by 2021.

Of particular concern is the country’s build up of its short-range tactical nuclear missiles; a response to Indian conventional superiority. Due to their design and deployment, these tactical nuclear weapons could potentially aggravate an already dangerous decade-long standoff between Pakistan and India.

Firstly, tactical nuclear weapons are less destructive than strategic nuclear weapons such as intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBM) and, almost exclusively target an enemy’s conventional forces. Because of their lower-yield and designated deployment, they may be launched in the belief that they constitute a more legitimate use of force than more destructive higher-yield weapons. This risk is especially high if ground commanders believe the weapon will stop an enemy’s conventional advances. However, the conflict could easily escalate as states respond to the use of tactical weapons with strategic weapons.

Secondly, because tactical nuclear weapons are deployed on the battlefield, the risk of an inadvertent launch due to misperception and/or miscommunication is relatively high. A battlefield commander in charge of a tactical missile unit could receive wrong information or misjudge the overall situation, which could easily lead to a nuclear launch. Considering these weapons would be deployed along the already fragile militarized Pakistan-India border, the danger of misperception in the Pakistani context is particularly real.

These inherent risks of tactical weapons have the potential to further destabilize an already unstable region. Relations between Pakistan and India worsened considerably following the 2008 Mumbai terrorist attacks by Pakistani militants and little progress has been made in repairing the rift. Instead, both countries have developed new strategies and weapon systems primarily designed for a military conflict with the other side.

The Obama administration most likely realizes the dangers of Pakistan’s buildup; however it has remained largely silent on the issue. Following a recent meeting between President Obama and Pakistani Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif three weeks ago, both sides issued a joint statement outlining their agreement on an array of issues. Aside from a relatively vague section on Pakistani nuclear security, nothing was mentioned about Pakistan’s nuclear arms growth or the wider military situation in South Asia.

This silence is primarily due to concerns about the larger US-Pakistan strategic relationship. The administration is aware of the national prestige associated with Pakistan’s nuclear weapons along with the pervasive belief within wider Pakistani society that the US wishes to acquire and destroy Islamabad’s nuclear arsenal. Weary of this, and weary of its problematic relationship with Pakistan since the assassination of Osama Bin Laden in 2011, the administration has avoided the issue in an attempt to keep Pakistani support for more immediate U.S. strategic interests. Chief among these are Afghanistan and the wider war against Al Qaeda and the Taliban.

Going forward, it is unclear whether the US will maintain this ‘strategic silence’ policy towards Pakistan’s ongoing nuclear buildup. Next year, US forces are set to leave Afghanistan, which will entail a reduction in Pakistan’s strategic value to Washington. As the administration’s regional interest shifts from the immediate to the long-term, it may find it difficult to ignore Pakistan’s growing nuclear arsenal.

How exactly this problem will be tackled is a significant challenge if the US does indeed decide to take action. Issuing sanctions in a manner analogous to those issued against Iran is unlikely to be pursued. Previous US sanctions against Pakistan while it was developing a nuclear capability did not stop the country from developing a nuclear weapon. Instead, these sanctions damaged US-Pakistani relations and caused widespread resentment among its population.

A more likely policy would be one where the US attempts to bring Pakistan and India into formal talks with one another. The negotiating table would serve as a confidence building measure for both sides, while at the same time providing a forum in which a formal arrangement that dampens mutual concerns could be worked out. On the Pakistani side, this dampening could persuade it to limit its tactical nuclear buildup. At the same time, the US would play the role of mediator, thereby avoiding the potentially negative consequences of sanctions.

Whatever the policy response will be, it is clear that Pakistan’s build up demands some form of US action. The distressing implications of Pakistan’s policy will become too great for the current US silence to be maintained – or at least it should.

Rethinking Nuclear South Asia: The Arms Race in India and Pakistan

On Wednesday, November 27, Pakistan test-fired the Ghauri ballistic missile (also known as the Hatf-V), which has a reported range of 810 miles. This isn’t game-changing news in itself, as the Ghauri was first tested back in 1998, and Pakistan has conducted seven other missile tests this year alone. Still, the recent test is a reminder that South Asia increasingly looks to be a more volatile nuclear flashpoint than Iran or North Korea.

Here’s a telling fact: the Ghauri missile that was tested this week is named after Afghan king Shahbuddin Ghauri, who conquered parts of India in the 12th century and established Muslim rule there. If that isn’t enough symbolism for you, consider this: the Ghauriwas specifically developed to counter India’s Prithvi missile – and Prithvi Raj Chauhan was the name of the Hindu ruler that Ghauri conquered.

The symbolic naming of the missiles tells us a lot about the underlying intensity of the India-Pakistan conflict, described just this week by Yale professor Paul Bracken as a “problem from hell.” Discussions about Pakistan among Western experts often revolve around the potential for Pakistani weapons to fall into the hands of terrorists, given the Pakistani government’s instability and its ties to terrorist groups. In 2010, a study by Harvard University’s Belfer Centre highlighted the nuclear terrorism danger, arguing that Pakistan’s nuclear arsenal “faces a greater threat from Islamic extremists seeking nuclear weapons than any other nuclear stockpile on earth.”

But in focusing on terrorism, are we overlooking the broader problem of the nuclear standoff in South Asia? In September, Tom Hundley argued in Foreign Policy that perhaps we should be more worried about a South Asian nuclear arms race than we are about loose Pakistani nukes. Hundley pointed out that the situation on the subcontinent in some ways poses a greater risk than the US-USSR Cold War standoff – unlike the US and the USSR, India and Pakistan are in close geographic proximity, have already fought a number of wars, and haven’t put in place crisis-management measures like the Moscow-Washington hotline.

Such concerns echo those of Stimson Center co-founder Michael Krepon, a South Asia expert who has been arguing for some time that South Asia is an exceptional case because of the presence of extremist groups, the lack of joint efforts at counter-proliferation (such as arms control treaties), and the added factor of neighboring China, which is a main focus of India’s security concerns.

Indeed, recent shifts in the two states’ military and nuclear doctrines point to the distinctive nature of the South Asian arms race. In the early 2000s, India established its controversial “Cold Start” doctrine, which allowed for retaliation against terrorist attacks through conventional strikes on the India-Pakistan border. Cold Start was developed specifically in response to the Pakistani-backed attack on the Indian Parliament in 2001.

In other words, the doctrine is the unique product of Pakistan’s sponsorship of terrorist activity and the fact that India and Pakistan are neighbors. And although some observers have pointed out that we shouldn’t overstate the importance of Cold Start, the fact is that it played right into what some have called Pakistan’s “paranoid” national security calculus. Cold Start led Pakistan to place a greater strategic emphasis on tactical nuclear weapons.

There’s a lesson here for analysts in addition to “pay closer attention to South Asia.” More broadly, it’s important to keep in mind the limits of conventional frames when it comes to India and Pakistan. Comparisons with the US and the USSR only take us so far, and the common notion of a terrorist-rogue regime nexus isn’t the whole story, either. Yet at the same time, the Cold War should remind us of the dangers of overreliance on nuclear weapons and a mutually escalatory military posture. Moreover, the experience of the US-USSR standoff offers lessons about joint efforts at de-escalation and crisis management, such as arms treaties, the Incident at Sea agreement of 1972, and, of course, the famous hotline. We would all be wise to critically evaluate the narratives that inform our thinking on South Asia – not just every few months when a missile is fired, but in a sustained way that allows us to address this pressing challenge to global security.

Fact Sheet: Fifteen Foreign-Policy Challenges For the Next President

By Usha Sahay, Rachel Murawski, and Eve Hunter The October 22 presidential debate on national security will cover Afghanistan and Pakistan, Israel and Iran, China, the Middle East, as well as the general issue of “America’s role in the world.” These issues have made headlines in 2012, and been prominent on the campaign trail. But, […]